Java Virtual Threads Performance Study

The much-anticipated Virtual Threads feature finally included as a standard feature in Java 21 LTS, promising to revolutionize the Java ecosystem. This post aims to explore the performance implications of utilizing virtual threads.

Introduction

It is a known fact that application threads are expensive resources. Traditionally architects have leveraged thread pools to make efficient use of the threads. When a task needs to be executed, a thread is requested from the thread pool instead of creating a new thread from scratch. Once the task is complete, the thread is returned to the pool, so that other tasks can use the thread. While thread pools have proven effective, they come with the burden of maintenance.

One short-coming of using a thread pool arises when a substantial number of threads are required. Given that OS threads consume a considerable amount of memory, there’s a limit to the number of threads that can be generated. This limitation has led to scalability problems, particularly for I/O-bound applications.

Asynchronous programming has been the answer to scalability issues. Tasks typically wait in a queue and are processed by a pool of threads. The task initiator receives a future object and doesn’t wait for the task to complete, thus avoiding blocking. The future object is used to decide the next steps based on the task’s result. This approach eventually evolved into reactive programming, which I perceive as asynchronous programming with an added rate limiting feature (since task queues have size limits and cannot expand indefinitely).

While asynchronous programming offers benefits, it doesn’t come without its drawbacks. Asynchronous code is unfortunately much harder to read, understand and debug.

Virtual threads offer the prospect of scalability while maintaining the ease of readability and debugging.

The official JEP 444 page provides valuable insights into what virtual threads have to offer. I recommend that readers refer to the official JEP 444 page (see the references section). Now let’s jump to the performance study.

Methodology

A simple Spring Boot REST application has been created. This application features a single endpoint for adding users to a database table. Db interaction involves only an insert statement.

The application comes in three different versions:

- The first version is a traditional synchronous JDBC application that relies on OS threads.

- The second version, while still a synchronous JDBC application, utilizes virtual threads.

- The third version is a reactive application that eliminates blocking calls. It employs WebFlux and R2DBC for fully reactive execution.

To test the application’s performance, k6 is employed to simulate user load. The number of virtual users is gradually ramped up to 500, held steady for a period, and then gradually reduced. All three applications are tested under the same setting.

Monitoring Results

K6 Metrics

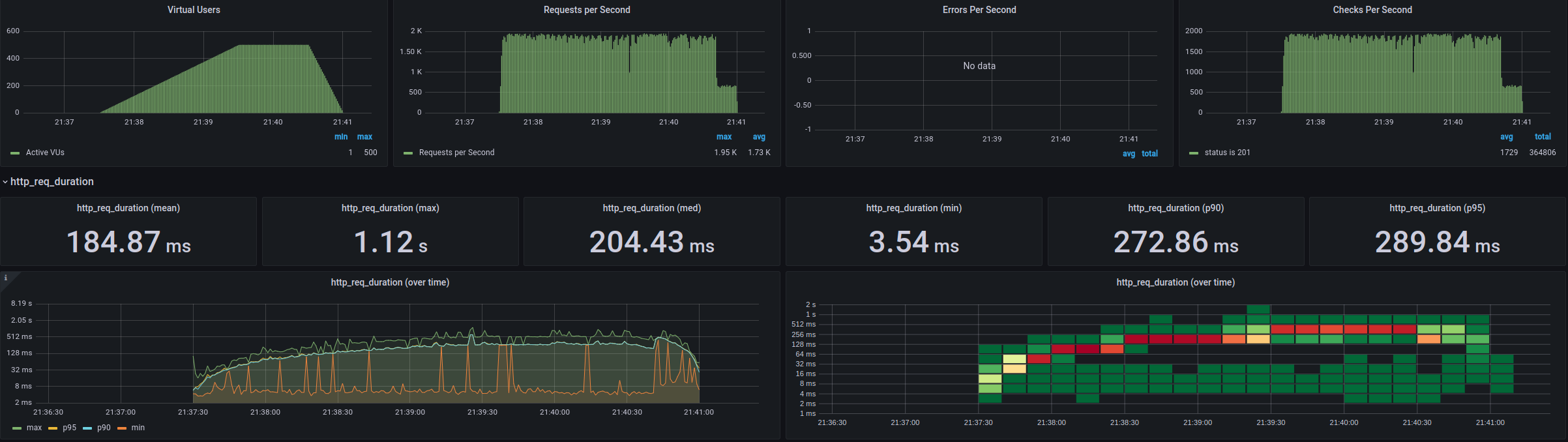

Application 1

Application 1

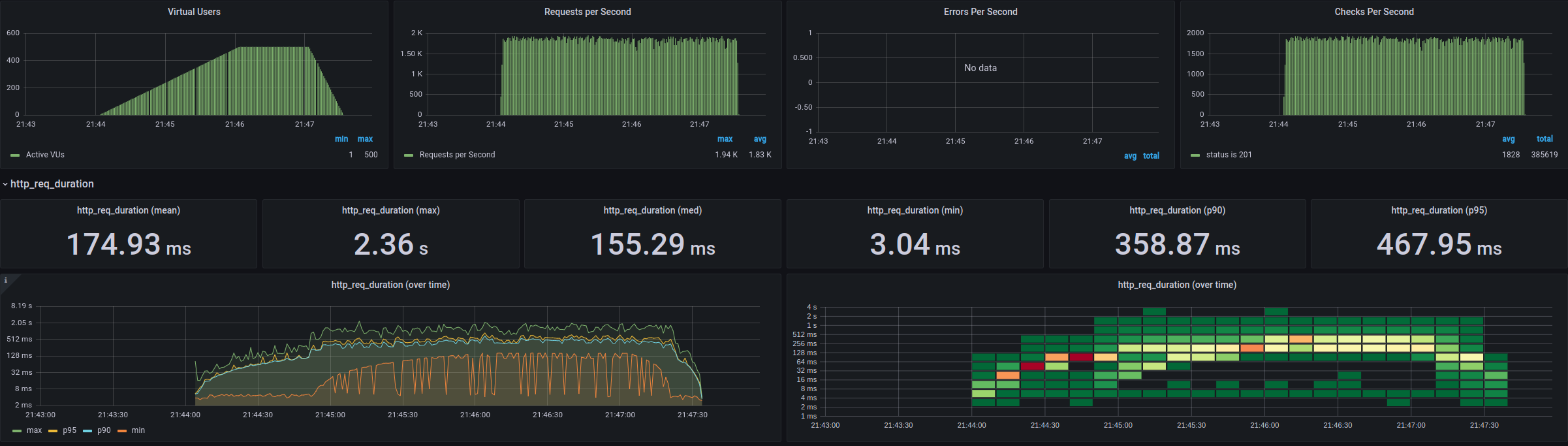

Application 2

Application 2

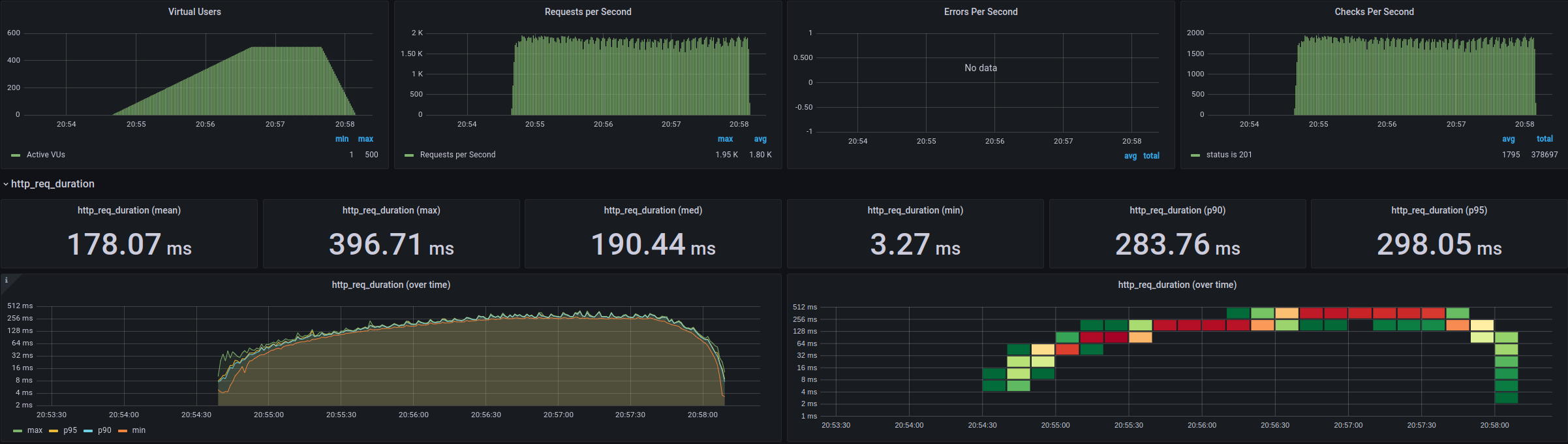

Application 3

Application 3

Application Metrics

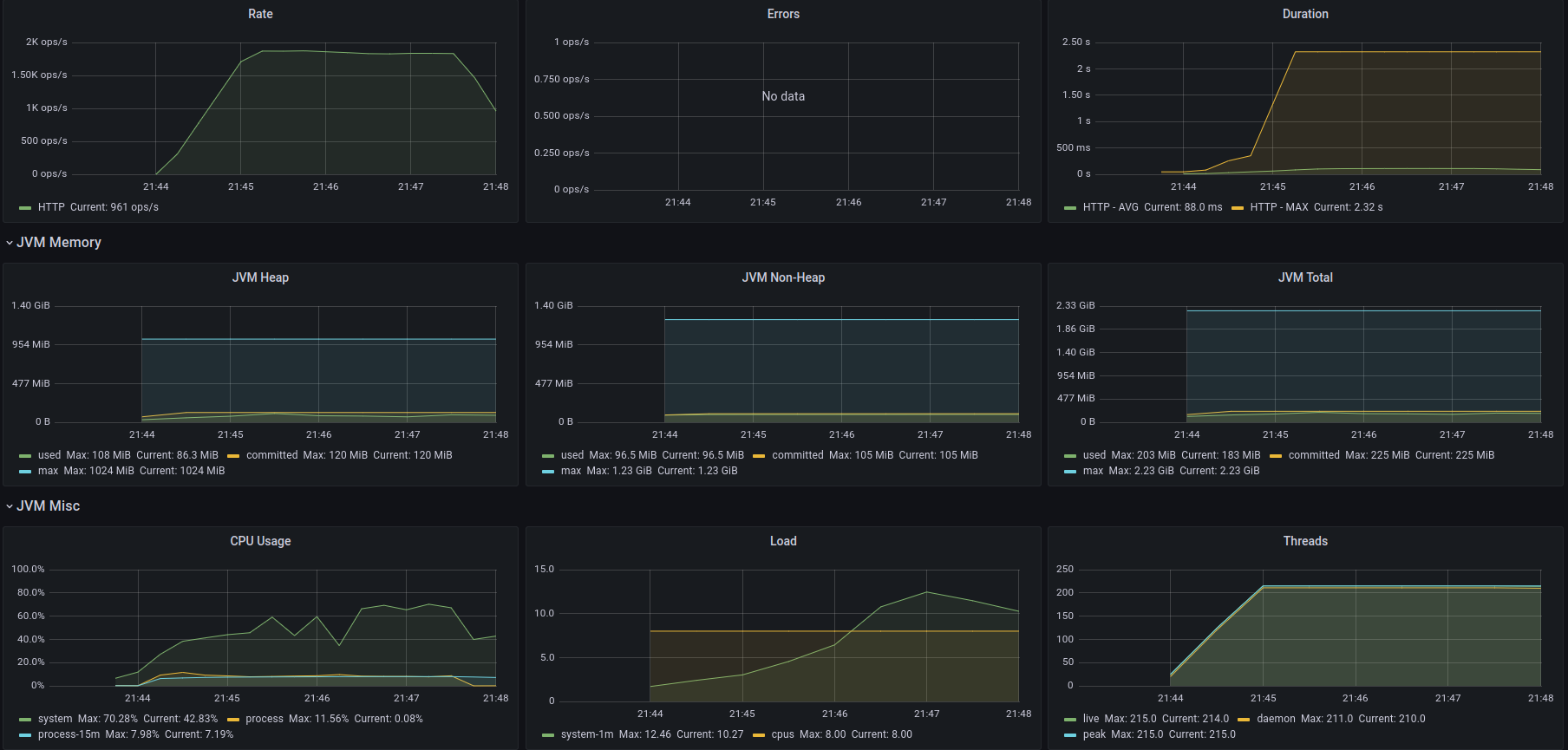

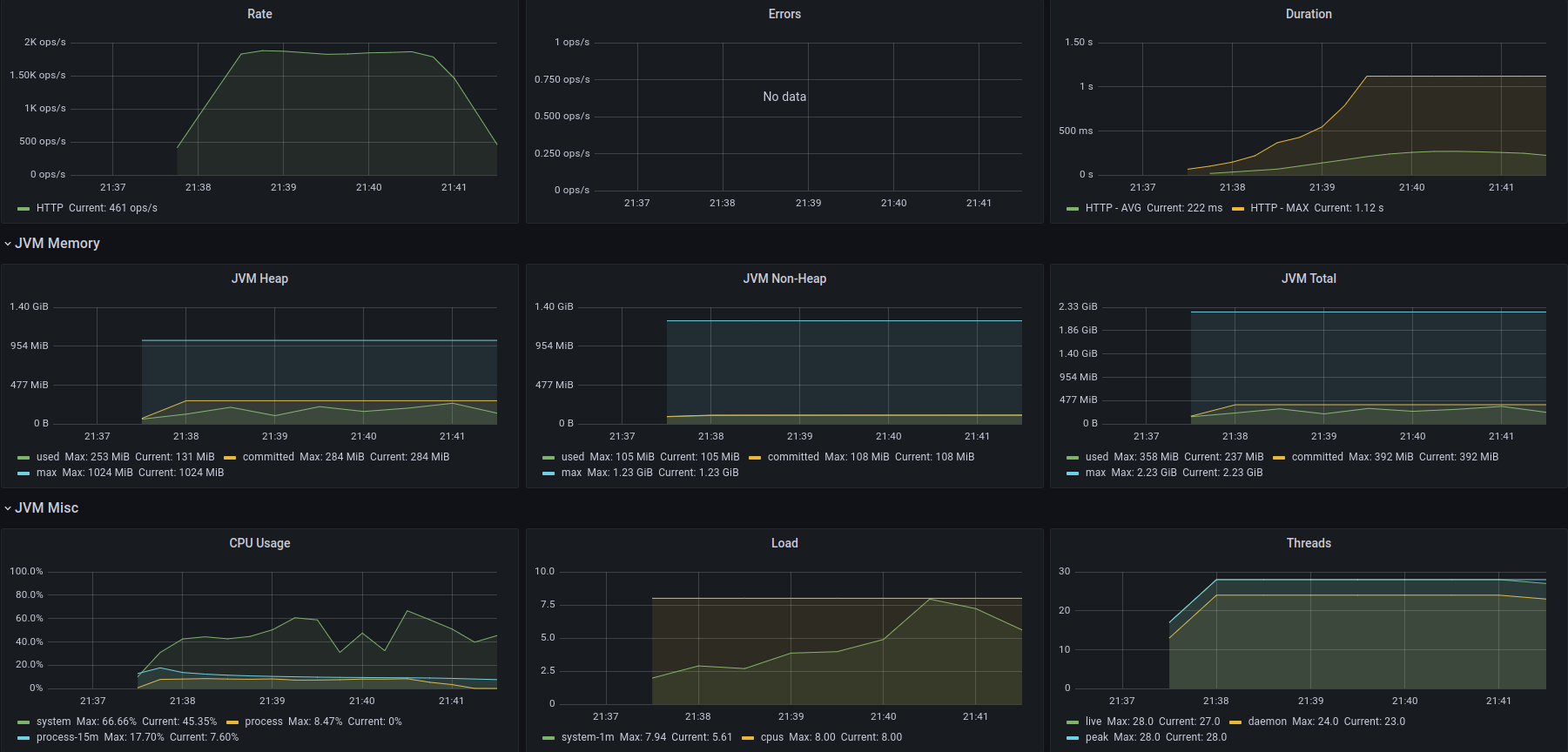

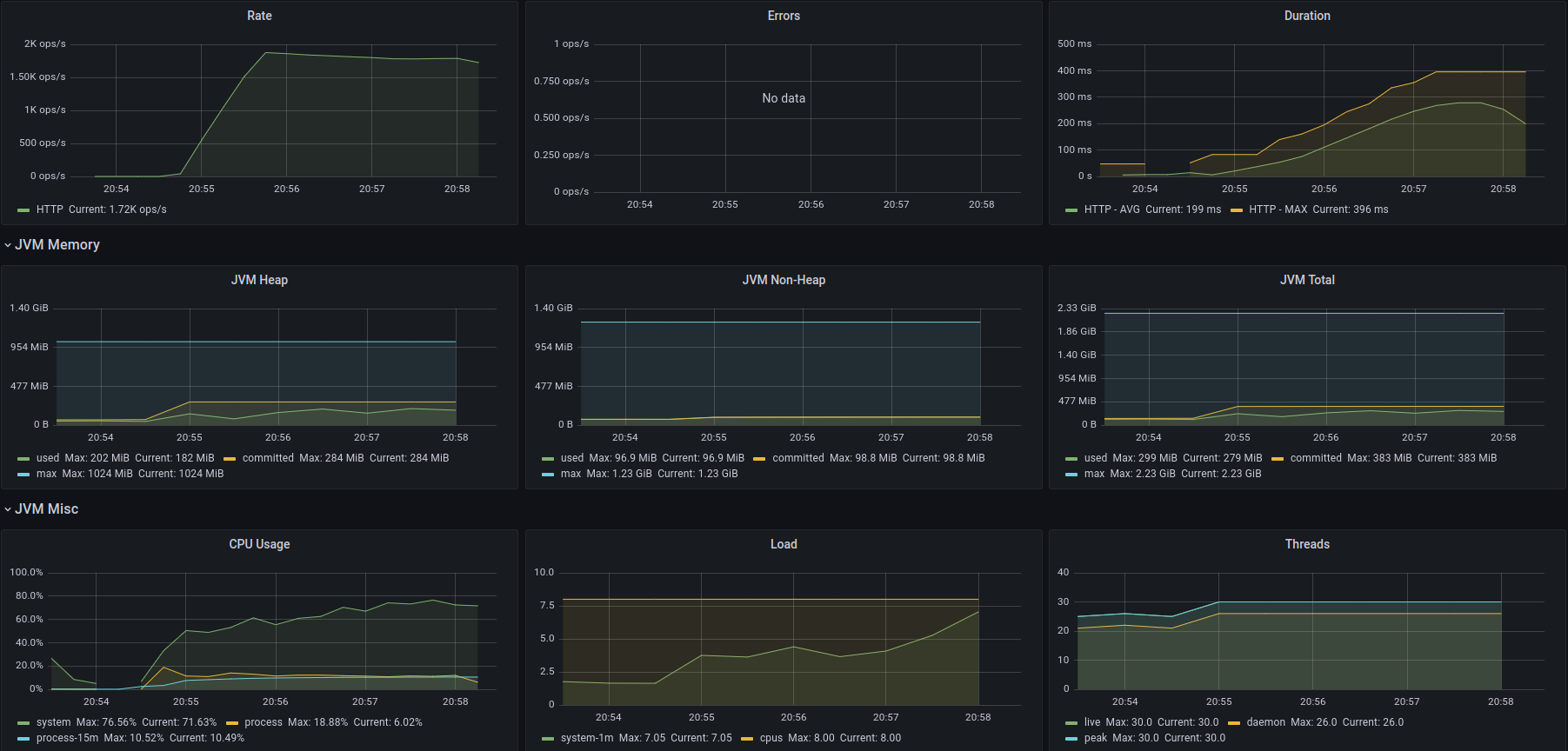

Application 1

Application 1

Application 2

Application 2

Application 3

Application 3

Analysis

All applications were configured similarly, with the exception of the thread settings. Therefore, it’s reasonable to ascribe all observed differences to these thread settings. (It turns out this is not completely correct, because R2DBC probably involves different approaches.)

Requests Per Second

In the tests, RPS happened to be just below 2K for all the applications. Due to a bottleneck I could not identify, K6 failed to move past this rate for the specific test configuration. Although the count of virtual users varied during the tests, it did not influence the RPS. I must admit that my expertise in K6 is limited, and my attempts to locate the bottleneck were unsuccessful.

Thread Count

As the number of users grows, the thread count of Application 1 also rises. The default limit for Tomcat threads in Spring Boot is 200, and as expected, the thread count ceases to increase around this number. Such an increase in thread count is not observed in Applications 2 and 3.

Despite the increase in thread count, there is no significant impact on the heap size, which remains relatively stable. It is believed that each thread contributes a 1m to memory consumption, which is definitely not the case. In contrast, Applications 2 and 3 consume more heap space, which is contrary to expectations. Repeated tests have consistently produced similar results, suggesting that this is not a mere coincidence but a phenomenon worth investigating. However, such an investigation falls outside the scope of this study.

Request Duration

This metric is crucial to consider as it directly impacts the user experience. The use of virtual threads demonstrated a noticeable influence on this metric.

Minimum request duration shows a clearly distinct behavior. Application 1 shows a relatively low minimum request duration until threads are saturated by the users. During the tests Application 2 manages to keep the minimum request duration low. Application 3 from the start has a minimum request duration close to the maximum request duration. This is an interesting observation and deserves further investigation. However, it is not within the scope of this study.

In all applications, p90 (also p95) and maximum request duration show similar behavior. As the test progresses, p90 moves past the 128ms mark and closes up to the 256ms mark. This is probably a result of database response times varying as pressure on DB resources tightens. Application 1 shows the worst durations after thread saturation occurs.

Application 3 shows very stable request durations. Application 1 and Application 2 show a relatively high gap between minimum and maximum request durations, which suggests database or database layer can reply to some requests very quickly. However, such low minimum request durations are not observed with Application 3. This suggests that there are differences in the behavior of the JDBC and R2DBC layers.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated that conventional java threads do not consume heap memory as much as anticipated. Virtual threads offer better scalability as they are not capped. Reactive design with WebFlux and R2DBC offers and interesting alternative that deserves further investigation.

If the results don’t fully convince you, feel free to conduct your own tests. The entire setup’s source code is available in my GitHub repository.